"Hello there," you say this morning,

Opening your eyes in the dark room

Once alight with your memories, your plans,

You're eager for the day to begin.

And when I kiss you - you smile -

"That makes it all rights."

Later:

How old am I?" And then

"Did we have some change in the calendar?"

I see your question is serious

"No, you actually lived all those eighty-nine years."

That night, in the dark again,

You whisper your good night.

"I will awaken one day into Knowing"

Liz Bugental

FOR JIM BUGENTAL

Authentic persons everywhere,

Be empathetic, show you care,

Transcend your existential guilt,

Don't let your will to meaning wilt,

Turn off TV, forsake the mall,

Come honor our Jim Bugental.

Though he has been here eight decades

His brilliance never dims or fades.

It's he who guides us straight and true,

Who sees the soul in each of you.

But who's behind those books of his?

It's not some wizard, no—it's Liz!

So let us cheer and celebrate

These lovebirds whom we think are great.

Tom Greening

Written many years ago for a party for Jim.

Published in Words Against the Void . Available from Amazon.com

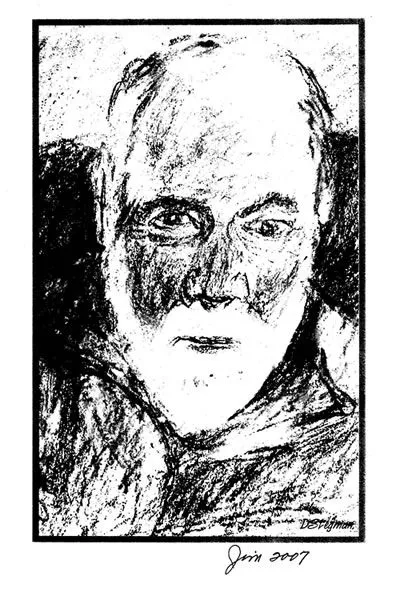

Sketch by Donna, family friend

There was a sickly centipede

whose life was full of pain and need.

He longed to be a healthy bug,

to live a life secure and smug,

so he sought out a therapist

who, sad to say, had somehow missed

the training that he could have used

so he would not be so confused.

If he'd been trained by Bugental

he would know how to do it all,

but never having learned from Jim

soon proved the nemesis of him.

Each time he tried to intervene

his client grew morose and mean.

He wasn't trained to help or treat

a client with so many feet--

his therapy was bound to fail.

So here's the moral to this tale:

It simply doesn't make good sense

to work beyond your competence.

It's not a prudent thing to do

to treat bugs with more feet than you.

Tom Greening

My (Smiling) Zen Master

My initial contact with Jim was in the winter of 1980, when I entered the Humanistic Psychology Institute (HPI). Although I was familiar with his landmark book The Search for Authenticity , I had little real knowledge of the man, and why he was so cherished. I remember how intrigued I was at that initial meeting. He had a wonderful facility for language and an incisive yet graceful style. I was also impressed by his romp through the hot tubs at that initial meeting, which took place at a Northern California retreat center, and his playful (one might say, impish) disposition. (In those early days at HPI retreats, it seemed like everybody got naked and dipped in the hot-tubs; for a kid from Cleveland, it was quite a scene—Jim, Rollo May, Stanley Krippner, Dick Farson—some of the greatest scholars in the land, all hopping around, splashing!)

My great fortune to connect with Jim took even loftier turns when I enrolled in and was accepted for a nine-month long mentorship course that Jim and the Institute had just initiated. In this course, five or six of us immersed ourselves in Jim’s work and being. We met in bimonthly seminars at some of the loveliest Bay Area retreats—i.e., Westerbeke Ranch, Forest Knolls—and we also, on occasion, met with some of Jim’s most illustrious colleagues, such as Rollo May, Irv Yalom, and Peter Koestenbaum. It was the perfect setting to sit at the feet of the master, and partake actively in his tutorials, but also, and equally, to discover what really set this master apart—his living, immediate presence. Although Jim’s lectures were good, his focus and intensity as a person were great. Indeed, it was at those seminars that I really learned the practice, the art, as Jim would say, of psychotherapy, and all that I’d learned before (with the exception of my own life-turning therapy), became completely subordinate.

My next auspicious engagement with Jim was in the wake of the mentorship. As it happened, Jim and Liz were just considering a new project at the time—a revival of their low-cost, existentially oriented counseling center called “Interlogue.” Jim and Liz had only three internship slots for this enterprise, and I was fortunate enough to be chosen, along with two other students. Everything I had learned during the mentorship now became concentrated and accentuated in the internship. Working with live clients, and having the privilege to engage with Jim and Liz as my supervisors, seemed almost dream-like, and yet the two of them could hardly have been more real. Their training, in fact, was intense, personal, and powerfully down-to-earth; as were their personalities. They were very well organized, to be sure, but this was tempered by an accessible air: a sense of family, even. I recall one night for example that I slept at the Interlogue office—with their permission, of course, and aside from the chill of the unheated building, I felt right at home.

Jim and I had a warm, profoundly appreciative relationship, but we also had our tensions. Some of these tensions were philosophical, some didactic, and some even Oedipal, but beyond all that, one impression stood the test of time--his smile; that loving, infectious, vexing, wonder-filled smile. And that smile—accompanied by laugh lines—only improved with time; particularly in his retirement years, when the ravages (as well as graces) of age predominated.

Recently, and in the aftermath of Jim’s death, I had the opportunity to participate in a therapy video series for the American Psychological Association at a Midwestern university. Nearby, I stayed in a little Holiday Inn, which is the very same hotel that hosted Jim for a similar assignment some 15 years prior. As I walked the grounds of the hotel, I felt Jim’s presence at my side. It was a gentle, loving presence, accompanied by an encouraging voice. That voice supported me but urged me to stay open to the further implications of the video; like its meaning for a more present-centered society, not just therapy profession. The voice didn’t go into specifics as to how or in what forms this present-centeredness could manifest, but the message was clear: there is always more, more than what is at first apparent.

That best sums up my experience of Jim: consistently present, but ever available to the “more” just beyond the apparent. And that is what I remember in his smile.

Kirk J. Schneider copyright Oct. 2008, Association for Humanistic Psychology Perspective